- Doomsday Scenario

- Posts

- Fleeing One Step Ahead of Fascism

Fleeing One Step Ahead of Fascism

Chilling warnings from 1930s Europe: "Reality is stronger than all our wishes"

Welcome to Doomsday Scenario, my regular column on national security, geopolitics, history, and—unfortunately—the fight for democracy in the Trump era. If you’re coming to this online, I hope you’ll consider subscribing. It’s easy—and free:

I often joke, darkly, that I write “history” books that get filed instead under “current events.” Over the last year, as I’ve worked on my new oral history of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bombings, there was one section in the book that always felt particularly chilling: The memories of the mostly Jewish refugee physicists who fled Hitler’s Europe to come to the United States ahead of the advancing cloak of fascism.

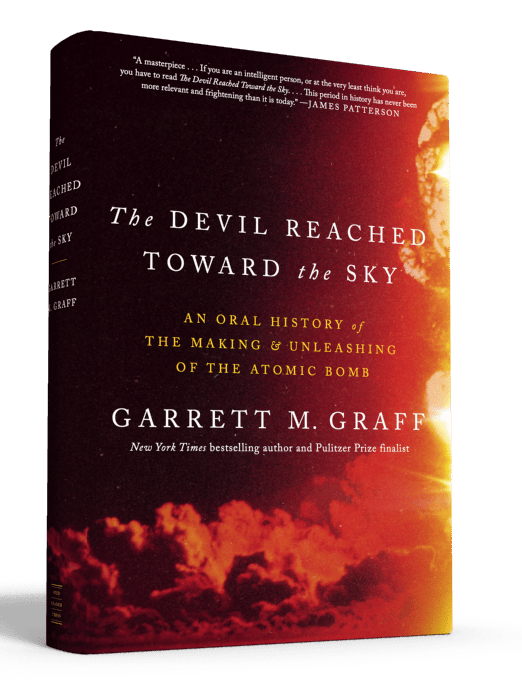

The book, THE DEVIL REACHED TOWARD THE SKY, comes out next week — (EDIT: you can order a signed copy here) — and given the spring and summer headlines about the backsliding of democracy here in the United States, I wanted to share what to me is one of the most urgent portions of the book, a chapter that takes place actually well before the work on the atomic bomb starts itself.

Today, we immediately associate the atomic bomb with Japan and the war in the Pacific, but it is actually rooted in the war in Europe and the threat of Adolf Hitler. The advances of physics through the 1930s were inseparable from the darkening clouds of far-right fascism on the European continent. The rise of Hitler and his National Socialist Party in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy destabilized much of Europe’s scientific progress, particularly as anti-Semitic politics and pogroms targeted many of the biggest names in physics.

Those fascist governments came to power alongside ruinous inflation caused by the fallout of World War I; over the course of 1923, the German mark fell from 400 to the dollar to 7,000 to finally 4.2 trillion to the dollar by November. Foreigners found themselves living like royalty as pensioners starved.

Over the years that followed, even as they helped lead groundbreaking discoveries around the structure of the atom, many of Europe’s top scientists watched with remarkable clarity as German democracy turned itself over — often much too willingly and easily — to Hitler, and they scoffed at their colleagues and friends who assured them, “Don’t worry, Hitler won’t be so bad — he won’t actually do the things he says he will.”

Any of that sound familiar?

This is their story — as you read, I suspect you, like me — will feel all too many parallels with how American society is proceeding today.

Albert Einstein, writing in December 1919: Antisemitism is strong here and political reaction is violent.

Werner Heisenberg, theoretical physicist, University of Leipzig: The end of the First World War had thrown Germany’s youth into a great turmoil. The reins of power had fallen from the hands of a deeply disillusioned older generation, and the younger one drew together in an attempt to blaze new paths, or at least to discover a new star by which they could guide their steps in the prevailing darkness.

The summer of 1922 ended on what, for me, was a rather saddening note. My teacher had suggested that I attend the Congress of German Scientists and Physicians in Leipzig, where Einstein, one of the chief speakers, would lecture on the general theory of relativity. The lecture theater was a large hall with doors on all sides. As I was about to enter, a young man pressed a red handbill into my hand, warning me against Einstein and relativity. The whole theory was said to be nothing but wild speculation, blown up by the Jewish press and entirely alien to the German spirit.

At first I thought the whole thing was the work of some lunatic, for madmen are wont to turn up at all big meetings. However, when I was told that the author was a man renowned for his experimental work I felt as if part of my world were collapsing. All along, I had been firmly convinced that science at least was above the kind of political strife that had led to the civil war in Munich, and of which I wished to have no further part. Now I made the sad discovery that men of weak or pathological character can inject their twisted political passions even into scientific life.

Walter Elsasser, physicist, Berlin, Germany: Once a week I took half a day off to go downtown and withdrew my [US dollar] allowance in marks. I at once bought enough food staples to last the week, for within three days, all the prices would have risen appreciably, by fifteen percent, say, so that my allowance would have run short. I was too young, much too callous, and too inexperienced to understand what this galloping inflation must have meant—actual starvation and misery—to people who had to live on pensions or other fixed incomes, or even to wage earners, especially those with children, whose pay lagged behind the rate of inflation.

Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Berlin correspondent, Chicago Daily News: The currency inflation was the worst blow to democracy in Germany. The German was told that “foreigners” were responsible for the inflation by their cruel greedy demands on Germany. The result of inflation was a sharp movement away from liberal democracy and toward patriotic reaction. (TWT, p. 15) Adolf Hitler saw the young Germans and won them to his banner, chiefly because he found them at the moment of their deepest material and spiritual despair. To their empty lives, he gave a meaning, however meretricious.

Rudolf Peierls, physicist, University of Leipzig: The economic situation in Germany was getting worse, unemployment was high, and political life was becoming more violent. Assassinations had been common during the whole period of the Weimar Republic, and now the brown shirts of the National Socialists were increasing in number and in aggressiveness. Yet few people had any inkling of the disaster that was imminent.

Sigmund Freud, neurologist, Vienna, Austria, writing December 7, 1930: We are moving toward bad times. I ought to ignore it with the apathy of old age, but I can’t help feeling sorry for my seven grandchildren.

Leo Szilard, physicist, Berlin, Germany: I reached the conclusion something would go wrong in Germany very early. I reached in 1931 the conclusion that Hitler would get into power, not because the forces of the Nazi revolution were so strong, but rather because I thought that there would be no resistance whatsoever.

Albert Einstein, writing in his diary, December 1931: I decided today that I shall essentially give up my Berlin position and shall be a bird of passage for the rest of my life.

Otto R. Frisch, physicist, Hamburg, Germany: I have never been politically conscious. In the early thirties I didn’t pay any attention to the general crisis atmosphere; with a sarcastic smile I observed the repeated changes of government and the much joked-about ineptness of Hindenburg, the famous general who had been made President of the Republic of Germany. When a fellow by name of Adolf Hitler was making speeches and starting a Party I paid no attention. Even when he became elected Chancellor I merely I shrugged my shoulders and thought, nothing gets eaten as hot as it is cooked, and he won’t be any worse than his predecessors.

Louis Fischer, correspondent, The Nation: How did Hitler come to power in Germany? Hitler’s policy, at home and abroad, has always been to reveal his plans. Hyper-suspicion of propaganda, however, led many people to doubt what he said. The Nazis boasted that they would rule Germany, and Hitler painted a picture of his future game. “Heads will roll,” he said. He would destroy democracy. Yet democracy tolerated him and helped him take office in order to destroy democracy. This peaceful death of German democracy is one of the strangest chapters in history. German democracy marched to its grave with eyes wide open, and singing, “Beware of Adolf Hitler.” Democracy is temperate. Its foe is extremism. In Germany, extremism was the thermometer of a sick social system and an ailing economy.

Eugene Wigner, physicist, University of Göttingen, Germany: Most Germans seemed strangely unconcerned with Hitler. They had not sought him, but when he came they said, “Well, the man is impressive. Let us see what he does.” Few of them expected him to lead Germany into a disastrous war. They watched with interest as he blamed their hardships on Jews and on other nations. But most of them thought he would stop short of a war. After all, Hitler had managed to take power in Germany without a war.

Bulletin, International News Service, January 30, 1933: Adolf Hitler, Nazi chieftain who began life as a house painter and street sweeper, achieved his life’s ambition today when he was appointed Chancellor of the Reich.

John Gunther, correspondent, Chicago Daily News: The night of February 27, 1933, a few days before the March 5 elections which were to confirm Hitler’s chancellorship, the building of the German Reichstag in Berlin was gutted by fire. This fire destroyed what remained of the German republic. It not only burned a public building; it incinerated the communist, social democratic, Catholic, and nationalist parties of Germany. It was discovered at about nine-fifteen on a winter evening back in 1933, but its embers are burning yet.

The Reichstag fire ruined a couple of million marks’ worth of glass and masonry. It also ruined some thousands of human lives. Logically, inevitably, the fire produced the immense Nazi electoral victory of March 5, the savageries of the subsequent Brown Terror, the persecution of the Jews, the offensive against Austria, the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the invasion of Poland, and the enormous process of Gleichschaltung, or forcible assimilation, which steamrollered over Germany. The fire turned an imposing edifice to dust and ashes. Also it turned to dust and ashes the lifework of many thousands of pacifists, liberals, democrats, socialists, decent-minded people of all sorts and classes. But for the fire the Nazis would never have gained so sweeping and crushing a victory. In the flames of the Reichstag fire disappeared the old Germany of Bismarck, William II, and the Weimar constitution. In its smoke arose Hitler’s Third Reich.

Leo Szilard: Hitler came into office in January ’33, and I had no doubt what would happen. I lived in the faculty club of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin-Dahlem and I had my suitcases packed. By this I mean that I had literally two suitcases standing in my room which were packed; the key was in it, and all I had to do was turn the key and leave when things got too bad. I was there when the Reichstagsbrand occurred, and I remember how difficult it was for people there to understand what was going on. A friend of mine, Michael Polanyi, who was director of a division of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry, like many other people took a very optimistic view of the situation. They all thought that civilized Germans would not stand for anything really rough happening.

Emilio Segrè, physicist, University of Rome: Hitler's rise to power was a major turning point in European affairs. Everybody who had knowledge of or contact with Germany could see that dire events were in the offing.

Eugene Wigner: Before 1933, I had never thought seriously about Hitler or the meaning of his rising political career. I must have seen bis photograph, but none of my friends attended his rallies or heard him speak on the radio. Very few Hungarians did. Hitler's vile speeches were printed in German and Hungarian newspapers, mostly Nazi papers. They attracted little attention. It was a time of great hardship in Germany, and hundreds of crackpots promoted their own programs for delivering Germany from its enemies.

Otto R. Frisch: I didn’t take Hitler at all seriously at first. I had the feeling: “Well, chancellors come and chancellors go, and he will be no worse than the rest of them.” Things began to change, and of course when the racial laws were published, by which people of partly or wholly Jewish origin had to be dismissed from the universities, I realized that my days were numbered.

Germans read an anti-Semitic bulletin board during the Nazi regime (Photo from Bundesarchiv, Bild 133-075 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Edgar Ansel Mowrer: The elimination of Jews from German public life—if not from Germany altogether—was one of the chief promises of National-Socialist propagandists and apparently rarely failed to elicit approval.

Ralph W. Barnes, correspondent, New York Herald Tribune, datelined Nuremberg, Germany, September 15, 1935: Stringent new laws depriving German Jews of all the rights of German citizens and prohibiting marriages between Jews and “Aryans” (Gentiles) were decreed by a subservient, cheering Reichstag here tonight, after an address by Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

Hermann Göring, Air Minister and Prussian Premier, German Reich: We must preserve the Germanic and Nordic purity of the race, and must protect our women and girls with every means at our disposal. In this pure blood stream will blossom forth a new era of Germanic happiness. Never again will we let our Germanism be infected and ruined by Jewish infiltration. Our newly won freedom requires a new symbol. The swastika has become for us a holy symbol. It is the anti-Jewish symbol of the world.

Eugene Wigner: The situation for Jews in Germany rapidly became intolerable. I would now need a permanent home outside Europe. I hoped against hope that fascism would subside and Hitler be replaced or subdued. But I did not expect it to happen. By 1933, I saw Europe as a sinking ship.

Leo Szilard: How quickly things move you can see from this: I took a train from Berlin to Vienna on a certain date, close to the first of April, 1933. The train was empty. The same train on the next day was over-crowded, was stopped at the frontier, the people had to get out, and everybody was interrogated by the Nazis. This just goes to show that if you want to succeed in this world you don’t have to be much cleverer than other people, you just have to be one day earlier than most people. This is all that it takes.

Werner Heisenberg: The golden age of atomic physics was now fast drawing to an end. In Germany political unrest was increasing. For a time I tried to close my eyes to the danger, to ignore the ugly scenes in the street. But when all is said and done, reality is stronger than all our wishes.

Otto R. Frisch: Disturbing rumors were rife. Some of my Jewish friends had warned me not to be out at night because Jews had been beaten up in the dark. I remember walking home late one night when I heard fast footsteps ring out in the empty street; I wondered if it was one of those anti-semitic brutes on the rampage. Of course to break into a run would have given me away at once; I kept my speed though the footsteps rapidly came nearer and finally pulled up beside me. A burly fellow in S.A. uniform pulled off his cap and greeted me with great politeness; it was the son of my landlady. He explained to me that he had to join this para-military force because otherwise he would not have been allowed to complete his law studies; there were many like him who disliked the Nazis but couldn’t afford not to join.

The persistent stories of concentration camps, of synagogues burnt, of beatings and torture, all were stoutly denied by the German newspapers as mere “horror propaganda” put out by the enemies of Germany. Some of my friends told me the stories were true, indeed that the truth was worse. But I wouldn’t believe that Germany had changed so suddenly and so horribly, and that all the newspapers could so consistently be telling lies.

Kurt Mendelssohn, chemist: Breslau, where I had a post at the university in 1933, was ahead of most German cities in establishing Nazi terror. We decided to leave forthwith, ostensibly to spend Easter in Berlin. In Berlin, I bought a ticket to London. When I woke up in [London] the sun was shining in my face. I had slept deeply, soundly, and long—for the first time in many weeks. The night before I had arrived in London and gone to bed without fear that at 3 a.m. a car with a couple of S.A. men would draw up and take me away.

Otto R. Frisch: In Copenhagen I heard for the first time the suggestion that the fire that had devastated the German Parliament had not been started by the accused Communist, van der Lubbe, but had been deliberately laid by the Nazis in order to work up public opinion against the Communists; it was an idea that startled me at first but then seemed plausible. After my return to Hamburg my one remaining colleague in the department, Knauer, gave me dinner at his lodgings and wanted to hear what people abroad said about the fire. Although he had become a Nazi Knauer had never let the anti-semitic party line interfere with our friendship. Quizzed about the fire I tried to hold my peace and talk of other things. But when he insisted I did tell him that people were convinced that the fire had been laid by the Nazis for political reasons. He was horrified. “But how can anybody think such a thing of people like Hitler or Göring; just look at their faces!”

Knauer kept his friendly and helpful attitude to the last and made my departure easy by finding a small freighter that was going to London and had one cabin for a passenger. On that cockleshell, on a windy day in October 1933, I left Germany with all my belongings in several trunks which kept sliding forth and back in my cabin as the ship rolled and pitched across the North Sea while I braced myself in my berth, unable to sleep.

Werner Heisenberg: When I returned to my Leipzig Institute at the beginning of the summer term of 1933, the rot had begun to spread. Several of my most capable colleagues had left Germany, others were preparing to flee. Even my brilliant assistant, Felix Bloch, had decided to emigrate, and I myself began to wonder whether there was any sense in staying on.

Bulletin, Associated Press, August 2, 1934: Adolf Hitler made himself absolute dictator of Germany today. He concentrated in his own hands the functions of President and of Chancellor as soon as the aged President Paul von Hindenburg had died at Neudeck.

Laura Fermi, spouse of physicist Enrico Fermi, Rome, Italy: It was almost unbelievable. Germans were the traditional foes of Italians, since the first World War, a fallen foe. The newly risen Fuhrer of Germany was held to be a none-too-intelligent imitator of the Duce, a puppet obediently waiting for directives from the Fascist Master. The puppet had taken some initiative of his own. In March, 1935, he had denounced the Versailles Treaty and declared that Germany would rearm. The Fuhrer had in store another of his spring surprise moves: in March, 1936, his troops occupied the demilitarized Rhineland. By then Mussolini was on bad terms with France and England, but dreaded and opposed a strong Germany.

Leo Szilard: When the German troops moved into the Rhineland and England advised France against invoking the Locarno pact [in March 1936], I knew that there would be war in Europe.

Edoardo Amaldi, physicist, lab of Enrico Fermi, University of Rome: “Physics as soma” [roughly, “physics is the cure,” a reference to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World] was our description of the work we performed while the general situation in Italy grew more and more bleak, first as a result of the Ethiopian campaign and then as Italy took part in the Spanish Civil War.

Laura Fermi: The following July, Germany and Italy found themselves together, unofficially fighting on the same side of the Spanish war. From then on, there was avowed friendship between the two dictators. Words with the quality of lovers' smiles were exchanged, and the Rome-Berlin Axis, another symbol devised by Mussolini, came into being on October 23, 1936.

Werner Heisenberg: The immediate prewar years, or rather what part of them I spent in Germany, struck me as a period of unspeakable loneliness. The Nazi regime had become so firmly entrenched that there was no longer the slightest hope of a change from within. At the same time, Germany became increasingly isolated, and it was obvious that resistance abroad was gathering momentum. A gigantic arms race had started, and it seemed only a question of time before the two camps clashed in open battle.

Emilio Segrè: Talking politics with American colleagues, I found an incomprehension of things European that was appalling to me. My partners in conversation had many different opinions, but most seemed convinced that what happened in Europe did not concern the United States, and that if the Americans minded their own business, they could avoid entanglements in European quarrels. It was, fundamentally, the isolationist thesis; they did not grasp Hitler's nature and his plans of world domination. These plans were the products of a deranged mind, but the disease had spread to a whole nation as powerful as Germany, and it was not something to trifle with. I strove to persuade isolationists that things were not as they hoped and believed.

Laura Fermi: On March 12, 1938, Hitler occupied Austria.

Eugene Wigner: Hitler’s campaign against the Jews cost him most of the greatest people I had studied with. If Hitler did not personally fire us all from our jobs, he made life unsafe for us in Nazi countries. And he forced us to follow politics. Many other important physicists fled as well, Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller, and Hans Bethe among them. Most of us resettled in the United States. Perhaps the United States should erect a great stone monument to Adolf Hitler for his dedication to advancing the American natural sciences. Not even Joseph Stalin scattered scientists like Hitler.

Thanks for reading — I hope you’ll consider preordering the book from an independent bookstore, Bookshop.org, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Books-a-Million, depending on your preference!

If you’ve listened to either of my previous oral histories on audiobook, this one is also amazing — and also features archival recordings and a full-cast with rockstar narrator Edoardo Ballerini. Get it on Libro.fm or Audible or wherever you get your audiobooks!

GMG

PS: If you want to hear more about my book, here’s an event I did earlier this month at the National World War II Museum: