- Doomsday Scenario

- Posts

- Were the atomic bombings necessary?

Were the atomic bombings necessary?

Today's 80th anniversary of the end of World War II revives a long-standing debate.

Welcome to Doomsday Scenario, my regular column on national security, geopolitics, history, and—unfortunately—the fight for democracy in the Trump era. I hope if you’re coming to this online, you’ll consider subscribing right here. It’s easy—and free:

It was never my intention that this newsletter be all Trump all the time — my interests and writing are usually much wider than that alone — so now it’s time for something completely different.

Eight decades ago, today, on the USS Missouri.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the official end of World War II, the surrender ceremonies aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. I’ll be speaking tonight about my oral histories of D-Day and the Manhattan Project at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library in Ann Arbor and then tomorrow night participating in Grand Rapids’ Greatest Generation celebration. Then it’s on to the National Book Festival in Washington, D.C., this week, the Cap Times Ideas Fest in Madison, Wisc., next week, and the Mississippi Book Festival the following weekend. If you’re attending any of those events, please come and say hi.

The most consistent and frequent question I’ve gotten in all of book talks over the last six weeks about the Manhattan Project and the atomic bombings is some version of: Were the atomic bombings necessary? Should we have dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

It was a question that I struggled to answer throughout writing THE DEVIL REACHED TOWARD THE SKY — and still struggle to answer now. I will say this: I had a more sure answer before I visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki earlier this year for book research.

I write in the introduction to the book that World War II was a conflict that shattered the lines of morality and the traditional divides in warfare between civilians and combatants. Much of the calculus of those final months of World War II boils down to a question posed by James D. Hornfischer, one of the premier modern scholars of the conflict: “The question of morality in warfare is vexing. Is there a moral way to kill someone? Is a bullet preferable to starvation, starvation to incineration?”

As I write about and explore in the book, the scientists and physicists of the Manhattan Project themselves struggled in the final months of the atomic bomb development with the morality of the bomb — many had signed up to the project and been motivated by fighting Hitler and by early 1945 it was clear the bomb was too late to be dropped on Berlin. Some objected to the use of the bomb against Japan — that wasn’t what they signed up for, so to speak — and organized petitions and lobbied against the bomb’s use, while others, who had family or friends also engaged in the war effort, first thought of the people they’d save rather than the lives the bomb would take. As I quote physicist Leona Wood, “I certainly do recall how I felt when the atomic bombs were used. My brother-in-law was captain of the first minesweeper scheduled into Sasebo Harbor. My brother was a Marine, with a flame thrower, on Okinawa. I’m sure these people would not have lasted in an invasion. I have no regrets. I think we did right, and we couldn’t have done it differently.”

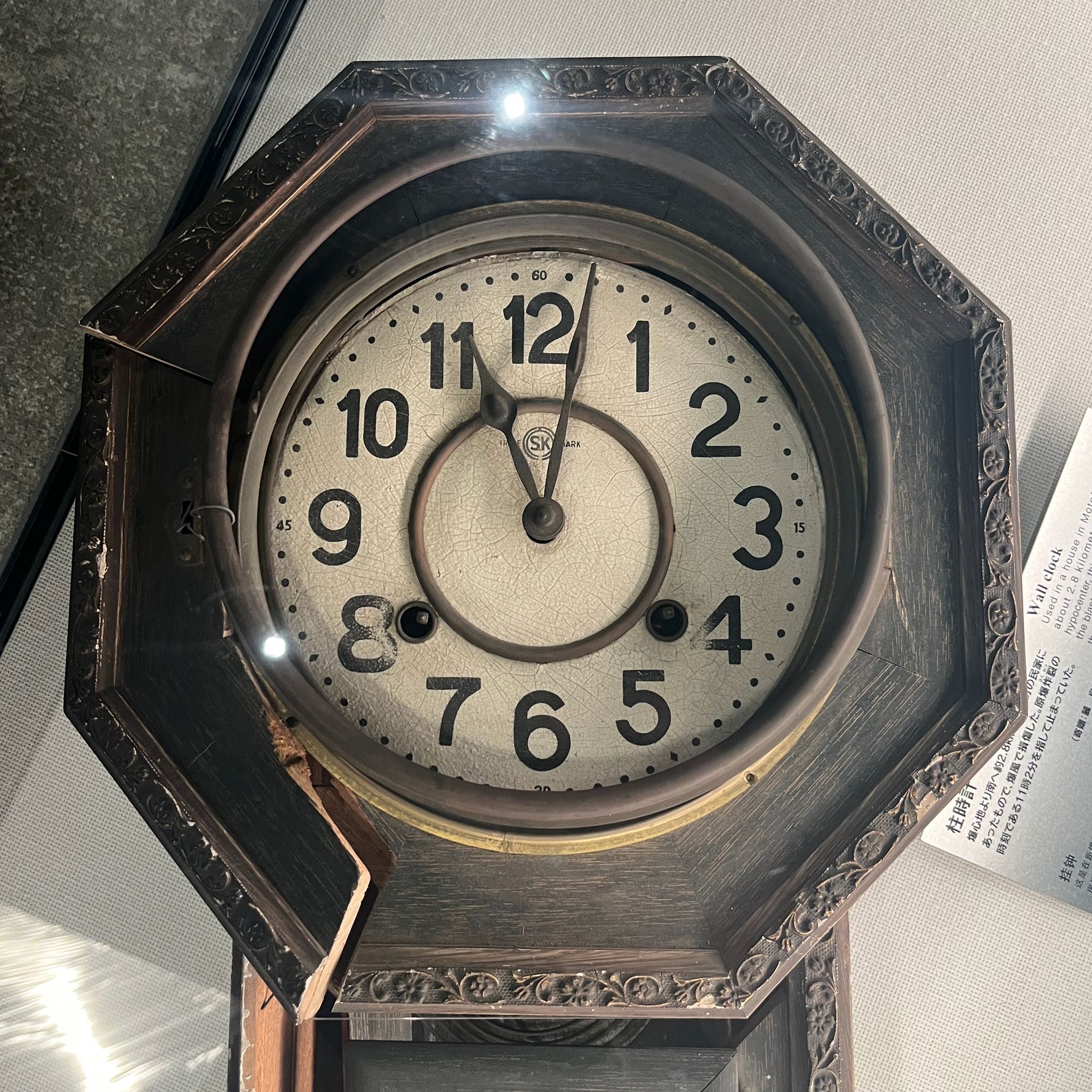

A stopped clock, on display in Nagasaki, from the moment the bomb dropped.

This debate has lasted for eight decades — in 1995, a plan by the Smithsonian to display the Hiroshima bomb plane, the B-29 Enola Gay, led to the widespread controversy and the resignation of the head of the Air & Space Museum — and presumably will continue forever precisely because there is no simple answer. There are, as with any major historical event, a thousand variations and unanswerable and unknowable questions tied up in it. (For instance: Did the US adequately convey privately its flexibility to the Potsdam Declaration?! Was using the bomb more about the end of World War II with Japan or about the start of the Cold War, with the Soviet Union?)

In recent years, new records and perspectives allows a more complete (and nuanced) answer about how the bomb fit into the final chapter of the war.

The first challenge is to put the decision to drop the bomb back in the context in which it was made. Today, we think of this question of “should they or shouldn’t they have” in a historical vacuum, and we approach the question as much more of a binary than any of the decision-makers did at the time.

The atomic bombings came in the closing act of a worldwide conflict that had killed in the neighborhood of 60 million people, some 15 million combatants and perhaps 45 million civilians. The numbers were so large that we round off the number of Chinese dead “only” to the closest five million — and even the total remains disputed. Some estimates put it closer to 70-80 million, meaning that the “rounding error” of the war’s dead was larger than the entire US population of New York State in 1940.

That death toll represented somewhere around two or three percent of the earth’s population at the time (2.3 billion). Today, an equivalent world death toll would reach in the neighborhood of 160 million to 200 million — more than the entire current population of Russia, Mexico, or Japan. The disparate ways humans killed each other across the world war probably has no equivalent in world conflict; in an episode mostly forgotten in the west, the Japanese unleashed biological weapons on China, including anthrax, typhoid, and the bubonic plague, that killed perhaps 300,000. Genocides, massacres, and famines killed tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, and even millions in places far from the headlines — Croatia, Algeria, Burma, Ethiopia.

As Edward Teller, who witnessed the Trinity explosion on July 16, 1945, reflected later, “As the sun rose on July 16, some of the worst horrors of modern history— the Holocaust and its extermination camps, the destruction of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo by fire-bombing, and all the personal savagery of the fighting throughout the world—were already common knowledge. Even without an atomic bomb, 1945 would have provided the capstone for a period of the worst inhumanities in modern history. People still ask, with the wisdom of hindsight: Didn’t you realize what you were doing when you worked on the atomic bomb? My reply is that I do not believe that any of us who worked on the bomb were without some thoughts about its possible consequences. But I would add: How could anyone who lived through that year look at the question of the atomic bomb’s effects without looking at many other questions? The year 1945 was a melange of events and questions, many of great emotional intensity, few directly related, all juxtaposed. Where is the person who can draw a reasonable lesson or a moral conclusion from the disparate events that took place around the end of World War II?”

That the bomb saved American lives has never been in question. In the earliest years of the postwar debate over the bombs’ “necessity,” US war planners like Secretary of War Henry Stimson put forward giant (and likely specious) casualty figures — estimates that the US invasion might lead to a half-million or even million casualties have come to dominate the debate. But there’s reason to be skeptical that the US’s paper invasion plans would have ever come to fruition — the numbers were so bad, in fact, that President Truman and other military leaders questioned whether they could avoid the invasion through a naval blockade that would starve the country instead. Yet even a widespread naval blockade and continued bombing by air would have yielded ongoing US deaths. Gen. George C. Marshall recalls how the nearer the US got to the home islands, the more brutal the fighting and the higher the toll of kamikaze suicide attacks: “By the end of June [1945] we had suffered 39,000 casualties in the Okinawa campaign, which included losses of over 10,000 among naval personnel of the supporting fleet. By the same date, 109,520 Japanese had been killed and 7,871 taken prisoner.”

More recently we’ve come to understand, too, how the bomb likely accelerated the end of the war on the Japanese side. Work by historians, including Evan Thomas in his 2023 book Road to Surrender, has documented how the imperialist wing of the Japanese military was set on fighting to the death; on the evening of August 14th , they attempted a coup and stormed the emperor’s palace to find and destroy his recorded surrender message before it could be aired to the Japanese people the following day. A lot of scholars argue that the Soviet Union’s entrance to the war against Japan in early August mattered more than the atomic bombings, but Emperor Hirohito — who proved the ultimate decision-maker — cited the bombs’ horror himself in his surrender message.

That elements of the Japanese military remained as defiant on ongoing fighting in the summer of 1945 remains astounding. Many Americans forget that in the course of 1945 the US was already engaged in a massive naval blockade of Japan, and by the summer of ’45 there was widespread famine approaching in Japan. Japan’s rice crop in 1945 collapsed, and across the country, many were living on just 1,000 to 1,500 calories a day. By the summer and going into the fall of 1945, Japan was on pace for a famine that would kill hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of civilians.

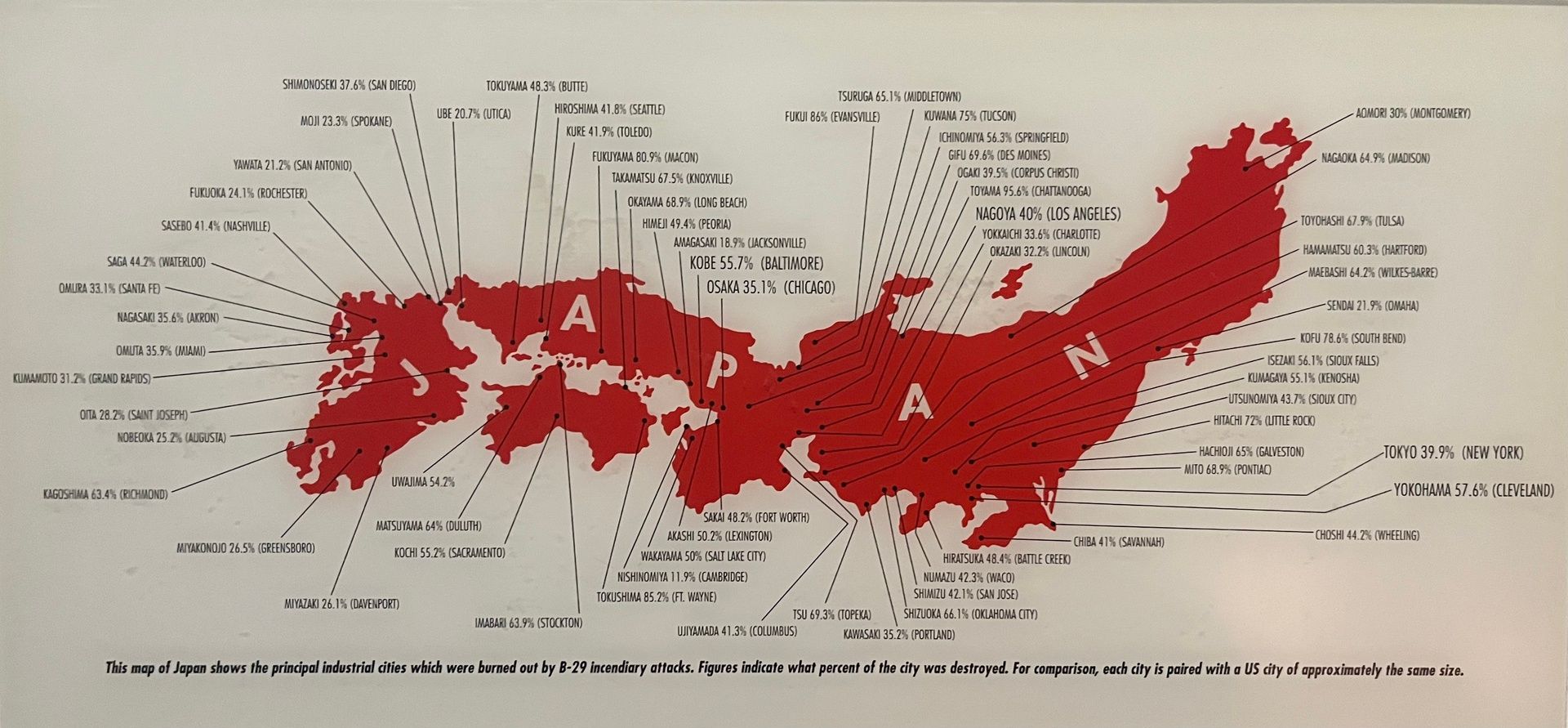

The list of Japanese cities firebombed (with US equivalents) at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

The US firebombing of Japanese cities over the spring and summer of 1945 was exerting its own tremendous toll. The deadliest single day of human conflict in history was not the dropping of either atomic bomb — it was OPERATION MEETINGHOUSE in March 1945, when the US firebombed Tokyo and burned much of the city to the ground, killing 100,000 Japanese in a single night. From there, the US went on to bomb a total of 66 cities — most of which Americans have never heard of; the chart in the National World War II Museum in New Orleans pairs each of those 66 cities with a US city of the same size for comparison. Some 40 percent of Nagoya, the size of Los Angeles, was burned. Nearly 70 percent of Shizuoka, a city of Des Moines, burned, as was 72 percent of Hitachi, the size of Little Rock. And so on and so on and so, night after night, city after city. The devastation was so massive that US war planners “saved” Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and a few other cities from the spring firebombing in order to demonstrate the power of the atomic bomb.

Even if the invasion of Japan known as OPERATION DOWNFALL — the first specific invasions were to be known as OLYMPIC and CORONET — didn’t happen in late ’45 or sometime in 1946, the naval blockade and firebombing campaign would have been extended for months longer with a large ongoing death toll on both sides.

Finally, it’s worth considering how US policymakers saw this decision — they never saw it as clear and stark a choice as we look back on it as today. Nor did they fully appreciate the horrors they were unleashing; the poison of radiation was little understood at the time. As nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein has smartly argued, “The plan was to bomb and to invade, and to have the Soviet invade, and to blockade, and so on. It was an ‘everything and the kitchen sink’ approach to ending the war with Japan.”

Yes, there remain complex questions about the US strategy in the war’s final weeks — Was a negotiated end to the war possible at some point if the US eased up on its “unconditional surrender” demand? Was the dropping of the atomic bomb the last act of World War II or the first act of the Cold War? — but all the evidence points to the conclusion that the atomic bomb was the only way that the war ends in August 1945.

Was it “necessary”? That’s a very different and harder question to answer — but it was the shortest path to the shortest war.

The Hiroshima Municipal Girl’s High School Monument in Hiroshima

At the same time, visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki underscores that it is right and correct that the central organizing principle of international geopolitics in the eight decades since has been to avoid ever using these weapons again. Visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki provokes a visceral and physical reaction. (That sheer horror is something that Tulsi Gabbard and I evidently have in common, oddly.) I found myself physically queasy going through the museum in Hiroshima, and sought out specially the monument honoring the Hiroshima Municipal Girl’s High School, which lost some 679 people, the most of any school in the city. It has a simple inscription on its: E=MC2, a reference to Einstein’s famous equation that unleashed the nuclear age. At the time, the American occupation prohibited discussion of the atomic bombing and that simplest of equations was a way around the American edict. Standing in front of the memorial, I cried.

Nuclear weapons are not like any other in the human arsenal. They are community and civilization destroying weapons, and we must in our time now follow through on the dream of the Hibakusha — the bomb-affected people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — to ensure that they are the last survivors of a nuclear weapon in human civilization.

I worry a lot that we’re standing at the edge of an age of geopolitical instability that will lead to additional nuclear proliferation; THE DEVIL REACHED TOWARD THE SKY is my second book on the awfulness of nuclear weapons, following on RAVEN ROCK, about the US government’s Cold War Doomsday plans — and any study of nuclear history shows that we’ve escaped nuclear war over the last eighty years as much by luck as by skill. We shouldn’t continue to gamble that our luck holds.

But that’s a subject for another column coming later this week!

GMG

PS: If you’ve found this useful, I hope you’ll consider subscribing and sharing this newsletter with a few friends: