- Doomsday Scenario

- Posts

- What We Lost When We Lost the Greatest Generation

What We Lost When We Lost the Greatest Generation

It's no coincidence that democracy is backsliding in the US exactly eighty years after the end of World War II.

Welcome to Doomsday Scenario, my regular column on national security, geopolitics, history, and—unfortunately—the fight for democracy in the Trump era. I hope if you’re coming to this online, you’ll consider subscribing right here. It’s easy—and free:

The scale and scope of World War II is almost impossible to fathom—a war that consumed entire continents and raged across nearly the full scope of the Pacific, an ocean that covers a full third of the earth’s surface, with battles from the Aleutian Islands to Hawaii to the coast of Australia. Estimates of the war’s full toll stretch north of sixty million, including 15 million combatants and 45 million civilians, largely Chinese and Russian, as well as the six million Jewish people killed in the Holocaust. Perhaps two million died in the battle of Stalingrad alone, and in a single night of firebombing, the US killed around 100,000 people in Tokyo, the deadliest single night of warfare in human history.

Growing up in the 1980s, I remember the Veterans’ Day and Memorial Day parades filled with World War II veterans — like my neighbor, Mr. Washburn — but this month’s 80th anniversary of the end of the war feels especially poignant as it marks an unofficial final passing of the generation who won that greatest of all wars. The National World War II Museum estimates that less than one percent of the US’s 16.4 million veterans from that war are still alive. Only about 200 D-Day veterans returned to Normandy for last year’s 80th anniversary commemorations. Many moments already belong entirely to history. Capt. Charles D. “Don” Albury, the last surviving aircrew member to witness both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, died in May 2009.

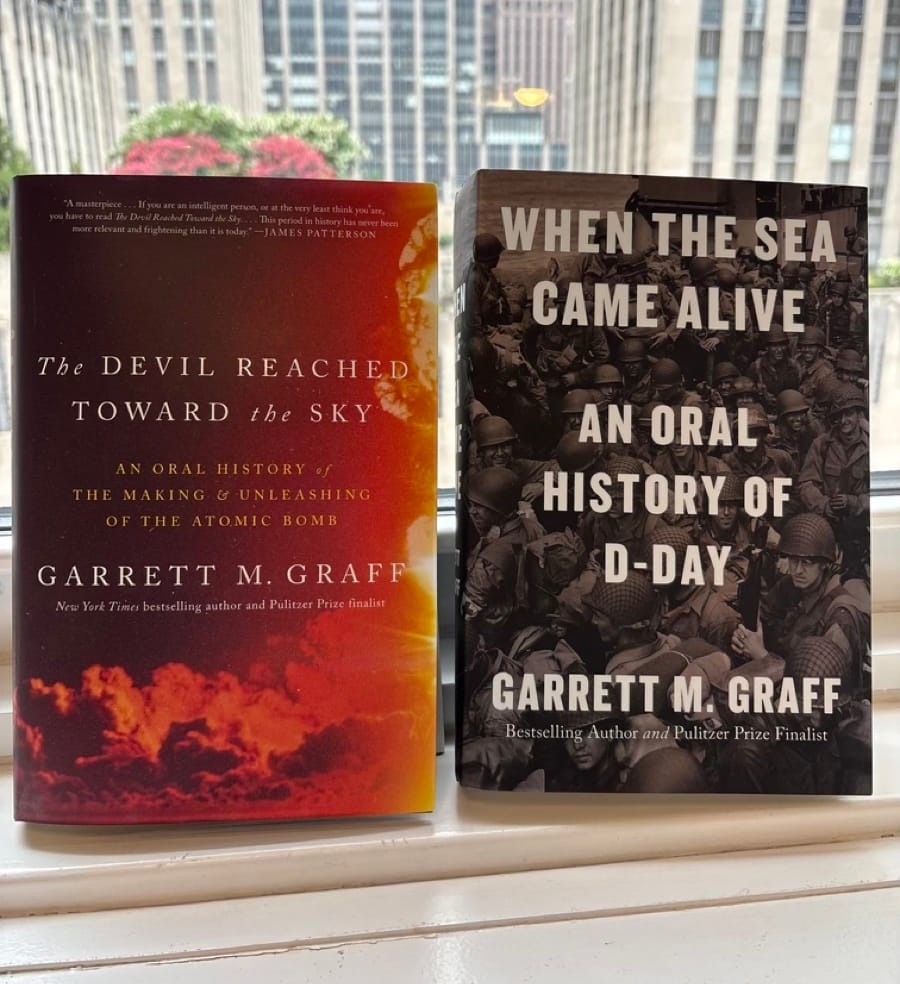

I’ve spent much of the last few years working on oral histories of D-Day, WHEN THE SEA CAME ALIVE, which published last year, and, more recently, on the Manhattan Project and the atomic bombings — a book, THE DEVIL REACHED TOWARD THE SKY, that publishes today.

Along the way, as I’ve watched the modern-news unfold, I’ve come to believe that in losing the World War II generation, we are losing more than just the memories of combat in Europe, Africa, and the Pacific, or the memories of working in homefront factories building aircraft in Willow Run in Michigan, landing craft at Higgins Industries in New Orleans, or manufacturing uranium in Oak Ridge, Tenn., as part of the war’s inner-most secret, the Manhattan Project.

We are losing, too, the memory and experience of what it means to fight fascism and authoritarianism.

It doesn’t seem a coincidence that the US is watching democracy unwind here at home and flirting with authoritarianism fascism exactly 80 years after the end of World War II. We are in the process of losing the last of the generation who fought to rid the world of fascism and then fought to build an alternate world order.

Losing the last of Greatest Generation means we are losing the last of the generation who understand just how evil actual fascism is, how hard it is to rid the world of authoritarian governments once they’re established, and how hard it is to build a successful alternative.

Losing the Greatest Generation means we are losing the last of the men who stormed ashore at D-Day, the last ones who fought for every bloody square meter of Pacific jungle, and the last of the men who fought their way into Berlin and liberated Nazi concentration camps, seeing first-hand the worst humans can do to one another.

But that also means that we’re losing the generation who had the understanding and magnanimity and saw the necessity to build what came next — the men and women who pushed to found the United Nations and NATO, to implement the Marshall Plan and reconstruct Europe and rebuild Japan, and to build on the Bretton Woods agreement with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and to found international aid efforts like USAID and the Peace Corps. It was a generation that, at home too, understood the unique opportunity and benefit that would come from investing in science and education, from building government partnerships and support for higher education and medicine.

They were a generation not just of fighters, but of builders and dreamers.

The Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri.

It’s easy to look eight decades later at these institutions and criticize them as imperfect — to point out their very real flaws and say they’re too moribund or sclerotic to respond to modern day problems. It’s much harder to look at them and celebrate the reality that they worked — for eight decades, they have helped the world not be perfect but be better than it was, and, above all, they kept the peace, providing an all-but unprecedented period of global prosperity and peace between the great powers.

At the end of his presidency, Dwight Eisenhower — a man who had much to celebrate across his career — declared at the end of his time in the White House that perhaps his proudest accomplishment was seemingly the most basic: “We kept the peace. People ask how it happened—by God, it didn’t just happen.” Eisenhower never felt he got the credit for keeping the peace; going to war is easy, he knew — keeping the peace was harder.

It was a generation that uniquely understood that the natural state of the world and geopolitics was Hobbesian — freedom, democracy, and peace were not natural conditions of the world. They required active involvement, reinforcement, and hard, grinding, day-in, day-out effort to secure and extend.

Moreover, they knew intimately and up-close that the alternative to peace and freedom — fascism and war — was worse. America itself flirted with authoritarian fascism before. It’s easy to forget the model that Father Coughlin and other right-wing leaders of the 1930s offered Americans disenchanted with the Great Depression. But as fascism’s dark cloak descended across Europe — as secret police began demanding “papers, please” and kidnapping people off the streets and disappearing them to concentration camps, as Hitler’s government cracked down on free speech and expression, labeling critics “evil” enemies of the state, as they cut off access to science and education and demanded arts organizations fall in line, persecuted homosexuals, and closed borders to visitors — America made a different choice. It, along with a precious few allies like Great Britain, stood and fought for democracy when it counted most.

At the start of that effort, it’s worth remembering the war’s outcome has hardly foreordained — freedom hardly a certainty at the other end. Germany swept quickly right to the English Channel and seemed on the brink of overrunning Britain and all of Europe; Japan marched steadily to the very coast of Australia. Going through thousands of oral histories and memories for my new book on the atomic bomb, I stopped in my tracks when I got to the memory of Imperial Navy clerk Noda Mitsuharu, who recalled, “After the successful attack on Pearl Harbor, we sailors talked about the opportunities we might get. My dream was to go to San Francisco, and there head up the accounting department in the garrison unit after the occupation. All of us in the navy dreamed of going to America.”

The Manhattan Project itself was launched primarily out of fear that Adolf Hitler would get to the secret of the atomic bomb first, a revelation and invention that had it happened would have likely altered the course of the war. There’s a poignant quote from the fall of 1942, as a team at the University of Chicago races to build the world’s first chain reaction in the old squash courts under the football stadium, where experimental physicist Albert Wattenberg recalls, “All we did was to work and sleep, and sometimes we didn’t even get to eat meals. Sometimes we thought of why we were doing it; several times we discussed what we would do if the Nazis won—where we would try to hide in the United States? We were fairly certain we would be killed if we were caught. One morning very early Dr. Alvin Graves came in and wanted to take over what I was doing, although he wasn’t due in until late that afternoon. He said he just couldn’t sleep. He felt the Nazis were working, that they were pushing ahead to get there before us. We were in a real race, and he felt he shouldn’t be taking a day off.”

We now know that freedom and democracy prevailed, but for longer than we are comfortable to remember, it was a close-run thing. After, that generation of officials, policymakers, and veterans wanted to ensure that nothing like that ever happened again, and they devoted their entire working careers to that task. Building the postwar architecture that has secured the world and underpinned a tremendous economic boom and elevation of global standards of living — nowhere, ironically, more so than China — was neither easy nor a foregone conclusion after the war.

Their decisions and institutions were never perfect — America has never been a perfect country but for generations its goal has been to be one that gets better — and that postwar era reflected a broadly shared mission, aspiration, and belief that a safe and secure world was one that was good for Americans at home too.

For much of the last eight decades, the banal stability of our daily existence at home in the United States has been backstopped by a whole series of systems, programs, investments, and institutions built and fostered by this generation that allowed the US to be a superpower unlike any other country in world history. It’s a global order secured in places we never think about — places like NATO headquarters in Brussels and in small diplomatic missions in New York brownstones serving the United Nations, in USAID and Peace Corps projects at work in countries most Americans couldn’t locate on a map and overseas FBI “legal attaches” who work to make sure that the world’s worst criminals and terrorists can’t escape punishment, in the small office in the Pentagon that monitors the Moscow-Washington “Hotline” to avoid nuclear misunderstandings, in science and medical research labs at colleges and universities supported by government funding that are thinking not about the next quarter’s stock price but about advances still years or decades away, and in “freedom of navigation” patrols by Arleigh Burke-class navy destroyers through far-off bodies of water critical to global trade.

This system’s greatest achievements lie in things that don’t happen — recessions, depressions, and bank runs that never materialize, famines that don’t break out, wars that don’t start, nuclear conflicts that never occur, poverty that doesn’t crush lives, children who don’t die of measles, sanitariums filled with polio victims in iron lungs that don’t exist, and kids’ cavities that never develop. It’s easy to lose sight to what an achievement that has been precisely because, decade by decade, the awful things that used to happen all the time have slipped from living memory into history.

Sector by sector, institution by institution, this represents the incredibly hard-to-tell and hard-to-grasp story of planes that don’t crash. As the saying goes: It’s not news when a plane lands safely — it’s only news when they don’t. Planes used to crash a lot — and now, for a thousand big and small reasons, they don’t (as we were brutally reminded in January in Washington, D.C.). This metaphor applies across so much of our daily life, travel, economy, and world. We’ve gotten so used to it that we can’t fathom how much work year after year, by hundreds of thousands of bureaucrats, diplomats, soldiers, and scientists goes into making life boring — and none of us now are old enough to remember what life was like before.

The Manhattan Project’s architect, Gen. Leslie Groves. The outcome of World War II was, for longer than we want to remember, a close-run thing.

Since George H.W. Bush’s presidency, we have been governed for almost forty years by Baby Boomer presidents — Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump were all born in 1946 — who grew up under that umbrella of safety and security provided by their parents’ Greatest Generation, coming of age and working their careers in a golden age of American income equality, educational achievement, and social progress.

Instead of honoring that work and carrying it forward, though, today we have a generation of government leaders, from the White House to Capitol Hill to the Supreme Court to state houses across the country, who seem focused on speed-running the unwinding of those monumental human achievements. We are watching a new generation of reactionaries, neo-fascists, would-be authoritarians, and crack-pot science-conspiracy theorists who have grown up in the most peaceful, prosperous, and healthy age in human history undo some of the most magnanimous things humans have ever done for one another.

Just as that Greatest Generation passes, we as a society and country seem to be forgetting, again, that democracy, freedom, institutions, global friendships, and security alliances are not self-perpetuating; that fascism is not the answer to economic hardship, uncertainty, and dislocation at home; and that authoritarianism, once it takes root in the world, is incredibly costly, in blood and treasure, to expel.

Last time, nearly nine decades ago when fascism roared in Europe, the United States was able to march in and save the world. One of my favorite quotes from my D-Day book was Winston Churchill’s reaction to the attack on Pearl Harbor. The UK had fought Germany all but alone for two years at that point — and it wasn’t sure how much longer it could hold on. The night of December 7th , though, Churchill felt a wave of relief. The battle was joined.

“No American will think it wrong of me if I proclaim that to have the United States at our side was to me the greatest joy,” he recalled. “How long the war would last or in what fashion it would end, no man could tell, nor did I at this moment care. Hitler’s fate was sealed. Mussolini’s fate was sealed. As for the Japanese, they would be ground to powder. All the rest was merely the proper application of overwhelming force. No doubt it would take a long time. I thought of a remark which Edward Grey had made to me more than thirty years before—that the United States is like ‘a gigantic boiler. Once the fire is lighted under it there is no limit to the power it can generate.’ Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

This time, though, the situation may turn out worse both at home and for the world beyond.

If authoritarianism takes root here, there will be no United States to come and save us.

* * * *

Thanks for reading — I hope you’ll consider picking up my new book on the audacity of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb, as we mark this week the 80th As the Associated Press review said yesterday, “The story of the Atomic Age’s start is a fascinating one about the power of invention and a chilling one about its consequences. In The Devil Reached Toward the Sky, Garrett M. Graff skillfully tells both. The power of Graff’s oral history is the diversity of voices he relies upon in crafting a comprehensive history of the atomic bomb’s inception, creation and use during World War II. He creates a comprehensive account of what seems like a well-told piece of history by including voices that have been either little-heard or missed altogether in the eight decades since the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

GMG

PS: If you’ve found this useful, I hope you’ll consider subscribing and sharing this newsletter with a few friends: